The Language of Materials

Designer Seetal Solanki reimagines our relationship with the physical world—where algae becomes architecture and cooking reveals cosmic truths. Through her Material Atlas, she shows how substances speak (eggshells whisper fragility, concrete shouts resilience), urging us to seek alternatives over rigid solutions. "Why fly to Mars," she laughs, "when we haven’t loved the 160,000 materials already here?" A meditation on texture as language, and the erotic joy of truly sharing space—with objects, ecosystems, and each other. "To humanize materials is to remember we’re made of the same stuff."

5/8/202435 min read

In this tactile conversation, material researcher Seetal Solanki invites us to rethink our relationship with the physical world—where algae becomes architecture and cooking lessons reveal cosmic truths.

Key Threads:

Materials as Metaphors: Solanki’s Material Atlas reframes substances as living collaborators: "We don’t just use materials—we’re in dialogue with them."

The Erotic vs. Pornographic: Drawing on Audre Lorde, she distinguishes true connection (sharing a red toy) from hollow spectacle (sexualization without soul).

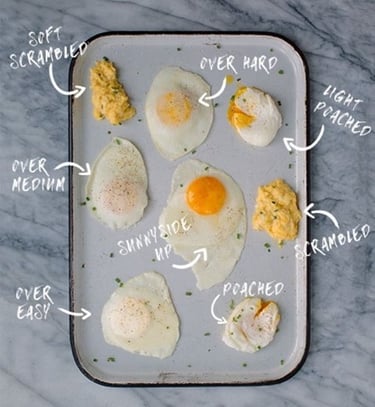

Eggs as Alchemy: Why "solutions" fail us—like scrambling an egg one way when it could be poached, fried, or baked into infinite forms. "Alternatives, not answers."

160,000 Materials & Counting: A playful indictment of consumerism: "Why fly to Mars when we haven’t learned to love the 160,000 materials already here?"

Why It Lingers:

Solanki’s vision is both ancestral and urgent—a call to "humanize materials" in an age of digital overload. As she traces her five-year-old self cooking to her current work, one truth emerges: "The erotic is just remembering how to share the world."

Read Full Transcript

Uzoma: Yeah. English.

Sheila: How?

Uzoma: You know, that's just one way of… or language generally.

Sheila: Okay.

Uzoma: That seems to take up so much space.

Sheila: I get it. Yeah, it is.

Uzoma: Looks like they used messages, which is cool. It is like a library for making things feel?

Sheila: Is it on their website?

Uzoma: Yeah, on their website. these shapes, like the feel tactile, even though they're in 2D?

Sheila: Yeah, that's what I was talking about this. Also, I was talking about the texture of the images that I'm seeing they are Like; it always feels like something that is more than the screen. Like, it comes out. It really respects the material that is being presented like on a digital thing.

Uzoma: Yeah.

Seetal: Hello

Sheila: Hi Seetal in your absence?

Seetal: Hi.

Uzoma: Hey Seetal.

Sheila: How are you?

Seetal: I'm very well, how are you?

Sheila: I'm gob smacked. I'm gob smacked into the matter of matter.

Seetal: Oh, lovely. You're going in already?

Uzoma: I was overwhelmed is my own word, which I feel like is gob smacked cousin.

Seetal: What was that? Sorry.

Uzoma: I said, as overwhelmed is my own word, which I feel……

Seetal: Oh stop it now

Sheila: Seetal it's amazing.

Uzoma: Yeah, it is, I'm almost at a loss for where to begin. So, I just want to ride…

Seetal: I will be speaking in a very casual manner, honestly, it's a quick chat.

Sheila: It is just a chat. But I think more than it's not even, I think it's just like sitting with the feelings that our bodies have been shifted into. Like, it's not, it's almost like we're not, we're so speechless. Because we're in, we're immersed in what you've put us into, like you've put us into the spirits and the lives of these materials. Now we are so in there that we need, like a moment to be like, wow, this whole world, we know it exists in that way. But it's so nice when we find other human beings while working hard to like, tell us it exists in that way.

Seetal: Yeah, it's simply reminding people that we've always kind of lived that way honestly. And I'm just simply presenting it in a way where it feels relatable. And so much of it is connected to a very spiritual way of being but actually, it's also very logical and practical, so I don't know, I feel like it's a no brainer. Like, how can we think that we are the most dominant species on this planet, when actually, you know, so many beings around us are telling us or speaking to us actually in a different language to what we're perhaps familiar with, on a human-to-human level. But so much of it is about listening and observing and awareness, I think.

Uzoma: Yeah.

Seetal: I guess that's consciousness to, you know, the ultimate degree but it's also just being present. Yeah, I really like this, this idea of an embodied intelligence somehow. And rather than a language of, you know, speaking or writing, I think there's so much that we ignore sometimes when it comes to other forms of languages. And I'm talking about things like intuition, or instinctive qualities too and your gut feeling, you know?

Uzoma: Yeah.

Seetal: And also like, the listening, the observing, and all of that's kind of interlinked, obviously. But then it comes to send, you know, how does something smell out of something taste. So, there's, so many other ways of talking to one another.

Sheila: Uzoma why did you laugh?

Uzoma: I’m laughing because just before you join the call Seetal, Sheila and I were on the matter website, and talking about the shapes on the home page and how, um, I commented that they feel very tactile, even though it's, you know, it's digital, and it's 2d, it feels like I'm still holding them. And Sheila was, actually before I said that Sheila was commenting about photography, and how it's a language unto itself. The way you can sort of like capture images and regard them through photography is a language unto itself. And then we start talking about like language, and like, how it's just put on this pedestal when they're all about communication and knowing. Um, so just hearing you see that is, it's kind of like, you weren't even there, but you were, you know?

Sheila: But I think that's what I was saying about what was so amazing about what, like you guys were doing is that it always feels like what's nice is that if it feels good to have someone who feels like they're on the same wheel of cognition around. So, no matter at what point I am understanding something, I can then still connect with you because either you've been there or you're just about to get there. So, it's never unintelligible like, it's always either pushing you further, or like taking you back into somewhere that like you miss and you recognize and I really like, there's some, that’s communication. That's understanding. And I was just reading an Audrey Lorde essay on uses of the erotic. And there's a part where she says, I'm looking for it to read it to you. There's a part where she's just talking about how the erotic is really about connection. Like she says, the erotic functions for me in several ways. And the first is in providing the power which comes from sharing deeply any pursuits with another person, the sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them and lessens the threat of their difference. And I just, why I love that so much is because when we think about the erotic as something that is always kind of like, corrupt. There's something so beautiful and innocent about this version of eroticism. That's like no actually what's erotic is just sharing with you.

Seetal: Yeah.

Sheila: Like when two people go to a park and then one person will offer their red toy and the other person will offer their blue toy like that's the seed of eroticism and what it should be, which is opposite to like, the pornographic, that's also what she's saying is that the pornographic is actually not the erotic it's actually the abuse of like, a signaling it's like taking the shell of something and then making that the essence of the thing but it's wrong like this. And I think even that kind of thing, or that kind of image is only made clearer by materials. I was reading your days interview. And one thing I wanted to ask is, do you see materials the same way that we're looking at language right as a metaphor and Uzoma and I we are seeing proverbs as almost putting language into a shape that makes a person's body feel the message being passed. Do you think that you use materials as a metaphor sort of like communicate something about humaneness?

Unknown Speaker: Most definitely. I would describe what I do as humanizing materials. And really, it's getting to know ourselves simply through materials. And I think, and getting to know material through ourselves. And there's such a common language that we speak to one another because we are constantly surrounded by them. And whether it's our cells and our bodies, or skin, or bones or the bed that we're sleeping on, you know, even when we're sleeping, we are in contact, and with materials, you know, so we have to kind of form a relationship that's based on care, respect, and actually love. Honestly, everything is connected by love. And I think the erotic is simply that. I think you're so right in saying that it's become pornographic. And I think that's because it's become sexualized, you know?

Sheila: Right.

Seetal: And I think that the, rather than it being sexual, it's being sexualized. And I think that's a really big difference in between, like, how we want to impose ourselves, or kind of our impressions on something. And it's really about changing perspective. And everything is about seeing the world through a different lens. And materials are a way to kind of navigate that. And so, I'm providing alternatives of how people can see the world and engage with the world relate with the world. But really, it's starting with ourselves. Yeah.

Sheila: I have a question. What do you remember as being the first material to give you an erotic feeling?

Seetal: Oh my God.

Sheila: …of impactful sensation and a connection to something?

Seetal: Food.

Sheila: Yes. Yes.

Seetal: Yeah. Its cooking has been such a big part of my life, and continues to be, I really have learned so much about the world through food. I started cooking when I was five.

Sheila: Wow.

Seetal: Yeah, very young.

Sheila: Seetal Is everything okay, why being you cooking?

Seetal: Hard times Sheila, hard times.

Sheila: It seems like. That's amazing, though. That's amazing.

Seetal: Yeah, it really was, at the time, not so much. But I was like, I learned so much about where ingredients came from, where to buy them, who to buy them from, how to prepare them, how to use everything, go component of the food and trying not to waste anything, or have no waste. If there were leftovers, they would be invigorated the following day into an entirely new dish. So, there was so much kind of learnings. I think this idea of formal learning and informal learning is how I've kind of bridged my practice together really, and food has been a really great vehicle for all of that, as well as like, you know, so much of my value system has come through my informal learning through my family upbringing, and, you know, values really, and how they've shaped myself and my own way of being with the world. And that is very spiritual one being brought up Hindu and I guess, seeing that we are aligned with the animal world, the plant world, all of these different kingdoms that exist here. Something that is being worshiped in Hinduism. And I'm not religious, I would say I would say I'm a spiritual. So, I have a deep respect for kind of seeing the world through those eyes as well Yeah.

Sheila: That's great. Thank you. Uzoma, you had a question.

Uzoma: Yeah. But just in response to that, I just think it's so amazing. Oh, ciao. Certainly. So, it sets us up for life. Because just hearing the stories, it's like it's so like, I can see the link between five-year-old you in the kitchen, and you know, the work you're doing now. And that appreciation for like, is clear. And I think that's really cool. And also, the distinction between formal and informal learning also sounds to me like the distinction between like, I don't know, east and west, or like, I was listening to something a few days ago. It was a matter Tia, who's a Taoists spiritual leader. And he was talking about how they've, like made certain discoveries at CERN, in Switzerland, that have validated like things that the Tao has known for hundreds of years. And he was like, really excited about it. And the person interviewing him was almost kind of confused, like, so like, your interest that like you like that science has discovered this. And he's like, yeah, like, so now there's like, Harmony that can exist now. Like it just it's like we can we are the better for it. And I feel like that's what is that the research sees that next practice as like, as well, is like, almost trying to bridge like, we talk about being bridges a lot like bridges between thinking and being and I think that is like a very exciting place to be. So, my question is connected to that. What I really. one of the things I really like about your work is how you've been able to translate to so well in the digital space that we also sort of inhabit now. And so, I just like to hear more about that, especially with like material Atlas, that project in particular. What is the secret behind this? Like, why did you choose to present it's in it's almost like a digital encyclopedia of materials that from the continent, so Yeah, that's just very interesting. I'd like to hear more.

Seetal: Yeah, there's so much to unpack there.

Sheila: Don’t worry Seetal, we can always have a follow up on our next podcast called Niggas isn’t shit. We can find a way to make it work.

Seetal: I am down

Sheila: They really aren’t.

Seetal: Okay, so I will begin by talking about informal and formal learning. Because I think that really will follow through to like how everything else has been or gets executed. So much. Yeah, I think we kind of ignore sometimes value systems, when we're kind of thinking about how we engage our working life and the rest of the world, or like, even relating to each other, I think, work is seen as something that we want to run away from. And actually, it doesn't have to be that way. It doesn't have to be TOEFL, it doesn't have to be something that we don't want to do, actually, I think this word work, or schooling, or learning, you know, all of these ways of thinking that it's compulsory. We're obliged to do these things. And actually, when we align our value systems, it's very philosophical, I guess, in terms of what I'm speaking about here, but it is all connected, connecting our entire selves. And understanding what we're made of. And what we're made of, are these learnings through informality thorough formality. And of formal learnings are what we've been taught at school, right? And that's being presented in a way where there's a right and there's a wrong and then say, you know, there's no kind of in between somehow, or there's no way of existing in this world between the informal and formal. We're just thinking about it in a very sort of linear way and also binary also colonial it's a very colonial way of learning, and they call it school.

Sheila: I just heard you describing that, like you would to a group alien, the aliens are like, Yeah, what's going on here? And you are like, Yeah, it's colonial learning, we call it both.

Unknown Speaker: Like, um, but actually, we're just learning, you know.

Sheila: Exactly.

Seetal: And we're learning about facts, history, how the world is made through geography, you know, like, all of these things are really valuable to learn about, and we’ll constantly be learning about those, you know, new histories are being formed all the time. And I think it's just aligning ourselves with how the rest of the world works. And not feeling too confined by there is a binary answer for something or I think with math’s, you can be quite creative as well, even though there is a conclusion at the end of it of sorts, right? But for me, it's so much about resolutions or providing alternatives, not solutions. So much of being taught is about finding a solution. And we're always being kind of pushed into a direction where we need to find a solution and that it's kind of a universal solution to solve the world's problems. And we don't even know what the problems are in the first place. Because we're just seeing it through one lens.

Sheila: So Seetal What’s the…Sorry, sorry, what's the difference between an alternative and a solution?

Seetal: Sure. So, for me, a solution is very fixed. And that's it, you'd like have basically solved an issue. And there's no other solution, or alternative way around it with a solution, you also will incur further problems, right? Because things change, things evolve, we evolve, and new kinds of issues are being created. Because our behaviors change our needs change. And all sorts of things. So, there's, we can't be fixed in the way that we think. And a solution is to fix and rigid, which doesn't actually provide very much, because it needs to be more nuanced? And if it's, because how can one solution be the answer for the entire world? It just doesn’t work because people's needs a different, there's cultural differences. There’re climate differences. And with all of these differences, we need to be more accepting of them, which evidence something that a solution is aware of. And I think for me, it's like okay, so what about providing options? What about providing alternatives, okay, we know that these issues exist. But these are the many ways in which they can be interpreted. And materials can offer those alternatives in many different forms. And materials are incredibly versatile, I would say. And that versatility is providing alternatives. It's like, for example, I use an analogy of like, eggs. Eggs can be… so it’s hard to describe a person working with materials and maybe in a design way is thinking of a cook or a chef and how they can work with one ingredient and process it in many different ways. And that processing is quite outcoming. Yeah, and by processing these ingredients, in different ways, whether you're baking, frying, scrambling, poaching, you know, all of these different processes end up with an entirely different texture and experience. You know, these sense, sensorial qualities that these processes kind of encouraged offer you with an entirely different application of sorts. You're like, Okay, so this texture is a bit more like, soft, it can be softer, can slimier it can be, you know, crumbly, even. And all sorts of things like that. And This is the same ingredient, it's just been processed differently. So, the example I would use is think about is algae. And algae can be food, fuel, textiles, color, insulation, architecture, so many things. And it's providing alternatives to our lives, really, and the way that we can perhaps live just with one ingredient. And this is really a conversation about potential, actually, because we as human beings are kind of pigeon holing ourselves, or we are being pigeon holed by others. When we get asked the question, what do you do for a living? And It’s the worst question to ask me honestly.

Sheila: Are you, exactly? it's true. It’s true. Someone was just tweeting about like, how they never really, like, understand why people take it so personal. And even me, I was like, it's such a sensitive thing for people to be asked that. But I also understand definitely that like, when a lot of people ask, what do you do for a living, maybe they expect to hear you solve a problem, like they expect the solution to your life. But it's like actually all, I have had alternative solutions to this whole fucking mystery of my life.

Seetal: Yeah, and I'm just like, these are the things that I align with. And also like, why I'm interested in, but what I do for a living is this, this, this and this, and this. And I'm like, and it's really hard. I don't blame people for being confused by sometimes what I do, or, but I present it in a way where I call myself a translator. Not a designer anymore. I mean, I'm still a designer, but really, I'm translating. And I think that feels really comforting to me, actually. And also feels like, it's never ending. And again, it's not fixed. It's, it feels like there's so many possibilities of trying to understand the many ways of translating, whether it be and this is all through language. And not just the polemical language, you know, what we're being taught in academia, and for me, it's so much about expression. Because as people, that's what we really want to do, it is express ourselves and feel comfortable doing so. And that's really a journey towards realizing our potential. And this is the same for materials because if we think about how many materials we have in the world, as 160,000 unique materials being manufactured industrially 160,000, what am I doing with them?

Sheila: I know what are we doing? What are we actually doing with them? Have you found out though?

Seetal: No, I'm just like, I'm so confused. I'm like, so why are we creating more? Why? On one hand, can we not understand how to work with the ones we already have? And what we have available to ourselves?

Sheila: So, do you basically mean why are we going to Mars?

Seetal: Yes. What is this about? I don’t understand

Sheila: Elon, Seetal on the phone. Can you imagine the conversation? Oh, my God. I would love this actually. I think it needs to happen ASAP. Like, Elon if you're listening to this podcast. Give Seetal a call. Please.

Seetal: Yeah. And we can have a conversation for sure.

Sheila: It would be awesome. Okay, before I even go into that there's something has been burning through my brain. So, all this stuff This translation between states between different states of one material, I am so interested in it, I remember, I went to my friend's house, and I wanted to drink tea, and there was only like Chinese red tea. So, I was like, what is red tea? And then as I was researching, I found out that red, green and black tea are all one leaf. Just oxidized in different time, which then brings me to the topic of time as our all-time almost as the mother or the parents of all material because if we're talking about translation, actually, we have to use like, the most constant force, or the most constant elements, in all those different materials is actually time. One of my favorite things to return to is how the Sahara wasn't always a desert. It was a freaking thriving ocean and they saw whales, they have evidence that even whales used to be or live around there. And then you have this thing that all my life, I have only known as a desert. Not even just called the Sahara, it's called the Sahara Desert. But once before, that desert wasn't attached to it. I have a quote that I actually want you to respond to. It's Tennessee Williams. And he says “time is the longest distance between two places.” What do you think about that? And the concept of time as a material?

Seetal: That’s beautiful. Do you mind repeating the quotes again for me?

Sheila: Yes. “Time is the longest distance between two places.”

Seetal: Yeah, I think time is the material, honestly. And it's the immaterial, actually, that we are kind of exposed to, but we kind of think about, so I'll kind of put it into this example, actually. So many materials are being designed for durability, right. And we think that that's way more valuable than designing a material that's actually meant to die quite quickly. And I think this idea of death in the material world, is something that we're quite afraid of, actually. And we see less value in something that has a short lifespan. And I'm saying that shouldn't be the case. Because, for example, like, single use plastic, is the primary example of all of this, you know, single use plastics, say for plastic bottles that we drink from can live up to 500 plus years, but it's being used in a form that is single use and disposable. So why are we not using a material that actually has a short life?

Sheila: Right.

Seetal: And I think there's this sense of long life or immortality is what we want to be striving for. And I think this idea of the death in the material, is seen as something we want to stay away from, much like the human life, right, we want to live as long as possible. And, you know, we will try and get there as in any which way we can. And sometimes it's forced as well, like most of these materials are meant to be designed for durability. There’re so many ways we can design materials, durability, modularity, versatility, biodegradability there's so many ways in which materials can live through different temporalities. And then it comes back to translation, it comes back to alternatives. And just strolling a different way of accepting them, actually accepting them for what they actually, the characteristics that they possess. And I think we start we need to start listening to them more and them telling us what they can do and achieve and what they want to be in life actually.

Sheila: This is so funny. I'm going to talk to my orange tonight.

Uzoma: I just got the image of like a dad like asking his child, like what do you want to be in life? And the child is like plastic.

Seetal: Exactly. What do you want to be when you grow up? You know that question,

Sheila: Yeah, that's true. That's time.

Seetal: Exactly.

Sheila: It takes a really good imagination to believe in time.

Seetal: Yeah.

Sheila: Because imagine talking to a plastic and being the only person to know that this plastic is actually going to last 500 years. But everybody's like, this person must be crazy to be talking to plastic. But we all know that, like, you can only get to that level, which is actually leading to my question, which has been in my head is, in what kind of emotional, spiritual and financial state do you have to be to sort of like, pay attention to the materials?

Uzoma: That is a good question.

Seetal: That is a great question. Great, wow. Now, how do I process…

Sheila: Because I'm just thinking, imagine, let's say we have a house girl now and the house girl hasn't, she finished formal education, like I don't know, in secondary school and for me that formal education is basically just time that is dedicated to learning. It's not that it's even superior or inferior, it's just that at least you have 8 to 5pm or 8- 2pm, where you can just be focused on learning something paying attention to your own life and not being responsible for catering to somebody else. So, you leave that, and then she comes to this house. And then instead of like, I don't know, we go downstairs to get something from the kitchen. And then we see her like talking to an orange, we would flip, we would be confused. But I do it. Somehow. People will be confused. But they're like, it's I mean, it's fine, because well, like she can still afford to like pay her rent if rent comes or so then certain level of other things around you that need to be shaped in such a way where paying attention to materials isn't the thing to sort of like, finally grant you banishment from your community, but it's something that you can still balance your life with.

Uzoma: Are you answering your question?

Sheila: No, I'm not answering. it's still a question. Because I'm just saying like, what do, how do we still? How do you guys maybe if you even take it personally? Like how do you Seetal create a state or exist in a state where it's affordable for you to pay attention to material?

Uzoma: I also wanted, when you asked the question initially, and this example that you gave is relevant, because this is something I think about a lot with regards, like with respect to Nigeria, and just setting, materially speaking, there's such an imbalance. So certain things that you can take for granted, that’s not necessarily the case for most people. And so yeah, just like I wanted to add that context to the question. Because I think it's really a thing that speaks to many places, like many parts of the world and not just here.

Unknown Speaker: For sure. So how I would approach this is to play. I don't necessarily think we need to be adding too much to people's lives in terms of like pressurizing them, or making them feel guilty or shameful, or any of these things because I think the way that we can integrate this way of thinking or perception into people's lives is quite simple. Honestly. I do it in a way where it's very playful. And all of that is to relationality and providing access. All of this is about access. And you know, materials have been positioned in an academic and scientific space for the longest time, and so much of that knowledge isn't necessarily accessible to the majority of people who haven't learned those things in school or university or anything like So all of this knowledge is very high level of sorts you know, the language that they speaking in these spaces isn’t very accessible at all. And you both speak of being bridges. This is exactly it, right. So, I'm bridging these worlds, but presenting it in a way, which feels relatable. And so much of this is about relationality, honestly, because all of this is there. That just, we just have to show it in a more relatable and accessible way. And that's still language.

Sheila: Yeah, I was, it's actually through what you're seeing is just reaching me spiritually, like in my bones, because I was just having a conversation with my sister just this morning. And we're talking about, oh, so someone wrote something about how like, if Mary, the mother of God could conceive of Jesus, who is God, then that means that she is God within herself, like that has to be part of the equation. So, there is no lesser, like, she's not a container for you to contain something so powerful, you are, in fact, a shape of that power. So, I was telling my sister, she was saying yes that when she's pregnant, she feels that God is closest to her because she feels that he is like, standing right next to her and actually forming the child within her. So, if she asked for something, it's most likely to get to him because he's right there. Like because her vision of God is that person. And so, I was just thinking, it's funny that I think the experiences we have with things like with matter, they all supposed to like they're all opening the door to our understanding of who we are. It's like we're taking different buses or different like bicycles to answer the question or solve the mystery of Who are we and what are we doing here? So, for my sister, it could be forming this child in her stomach. But for someone like Abubakar Fofana, it could be like translating leaves to bacteria to Indigo to die to fabric, like for the person picking the cotton, who is spinning it, it can be like, taking that and making it thread. So, whatever is almost available around you, like in an affordable way is supposed to be teach you about your strength in yourself. So, when people can't, for some reason they can't afford they're not even allowed to look around them and accept that what is affordable to them can also be highly technical, and be a really good teacher like something like how, for a longest time, we were taught to look down on our foods, like oh my god, Nigerian food smells bad. It's like, it's you're not cool. You're supposed to eat burgers and stuff like that. But they can turn around them and see a McDonald's like two blocks away. And that's next to them, and they can appreciate it. Well for us, we look around and see what's next to us. And we hate it, we're taught to say that this is not what we want. We want McDonald's, which is why when KFC came here, it was such a big deal… like people were going to KFC for Christmas. But like imagine doing that in America or London like that's already, you understand like you can't, you can't afford more? So, I don't know, I don't even know what question these lands on. I just wanted to add this to the conversation like what happens when people can’t look around them and accept that they have, they have teachers right in front of them.

Uzoma: Can I interject again?

Seetal: Please go ahead.

Uzoma: I think kind of related. And also going back to my earlier question around material Atlas. When you were speaking Seetal. I was. so, play is one of the materials in the alas and just when you were speaking about play, I was reminded of that. And so yeah, what’s my question? I think, so I like how it's like it being in the Atlas. It's almost like giving form. And it's almost like concretized like it's identified as a stream like it through like your technology as opposed to just like a thing that we know sort of happens. I mean, it does happen organically. But what I enjoy about this atlas is that you're giving.

Sheila: language

Uzoma: language Yes. You're like, it's like protocols and that's something that has been very like close to me just in the past few months thinking about the stuff we're thinking about. It's like, protocols can help, you know, language can help with just the work of reinventing, and we're talking about shifting from a solution-based mindset to kind of an alternative based mind set, protocols can help with that process. And so, I guess yeah, I kind of just want to hear more about that. And about identifying play as a thing, like capital letters P. I hope that makes sense.

Seetal: Um, yeah, I can kind of think about it from a perspective of the curriculum I've designed within my practice, because it has a relationship to the Atlas, the material Atlas. Because it really began with a workshop. I actually don’t even like that word, honestly. A session with 10 creators from 10 different countries in Sub Saharan Africa. And this was hosted with the British Council in the UK, and also Ellen MacArthur Foundation, and I was lucky matter was lucky enough to be able to like host a whole day session with these wonderful people and I started off with a material personality quiz that we designed. And it's really to get them to see themselves through material than the material qualities they possess, and they get to see themselves through, I guess a written language first. So, the qualities were framed around adjectives or verbs, rather than nouns. Because I didn't want them to be perceived as plastic or metal or glass. Because I wanted them to see themselves as possessing qualities around, I'm methodical, I'm empathetic, I'm caring. And all of these other qualities that human beings also possess, as well as material. Is it like if I identify, do you identify as a thing first, and then move to identifying as the qualities? Or how does the process work? Know that simply starting off with the qualities then you get asked a number of questions. And they're framed around whether you have an abundance mindset of scarcity mindset, you know, all of these different things. And all of the questions are very playful. So, one of them is like, are you a housecat? Or a chameleon? Or do you think like fungus or Eucalyptus or natural sorry, one of them? But anyway,

Sheila: What kind of mindset does cactus have a scarcity mindset or an abundance mindset?

Uzoma: Definitely an abundance mindset

Seetal: It was sorry, which one Sorry?

Sheila: Cactus.

Seetal: I think I said, what did I say fungus?

Sheila: Cactus generally? Because when you mentioned mindset, I just thought, it's so true that some materials have a scarcity mindset. And some have abundance, like, cactus to me just feel so rigid. It's like, I'm not breaking down my walls for anybody, right? Be self-sufficient to the day that I die, which is never.

Seetal: So, you could see it as abundance somehow. But then there's also a scarcity mindset. Because if it providing itself with so much, there's an abundance in that, but it passes in a selfish manner. It's true. Yeah, but then it's also providing life's other things. And, you know, it's providing amazing,

Sheila: Thank you. You changed my mind about practice, because I was like, these people need to like, they need to, they need help. Why are they so proud? Right.

Seetal: But then it's almost a lesson in thinking okay, so what are the qualities the characters possess, which I can relate to and maybe that I would like in my life, and be nice, okay. Yeah. To be cactus to learn from cactus. No,

Uzoma: No, this just reminded me of I ready brain picking, SP. And they were talking about this exercise they have friend did. I friend, the teacher, and so she asked, as students to identify the worst insect or I think animal, like the animal, the like the least. And to spend like the whole semester learning every single thing they could learn about the animal. And l thinks every week, like each week writing a poem about the animal, and by the end of the semester, just the perspectives, everybody's perspective had changed completely. Because when you spend that time just really mining something or someone for like, all its qualities, it’s that thing of like, everything is everything, I think earlier Seetal you spoke about love. And how it's a connector, and it's necessary in this translational work. And I think like when you spend so much time just like seeing the fullness of a thing, or person or place, there's no way you can’t, you develop a love for it. That's just how things work. It mirrors you and you appreciate that. So, shout out to cactus basically.

Sheila: Shout out to cactus.

Uzoma: I think we just have to form relationships towards other beings that are respectful honestly. And that respect can form care and love at some point, you know. But I think it really begins with respects and that is only really formed on trust.

Sheila: Yeah

Uzoma: Yeah.

Sheila: Is there a kind of? So, I have two questions, really, because when you were saying, you know, form it with materials that are, what did you say? You said that a caring? That’s kind of nice, and it made me remember that all materials as well, you know how you meet some humans that you want to make you feel safe, and some humans that don't make you feel safe.

Seetal: Yeah,

Sheila: But some materials are not really here to make us feel safe. And I remember that this is plants I have in me house that I've named spades. And every time I water it, it makes my hand like it gives me this feeling that I've been cut. So now I just stand for a big distance and throw some water on it. The reason I am keeping Yes, but it's because I just don't want them to say that I've killed a plant but left to me, you’d be gone. So, it's like we have a relationship of just distance. Like, at times, I feel bad for it as well, because in a way, I've romanticized all greenery as peaceful and loving. Maybe some really aren't. So, I think there's such a thin line between making this material something. It's like, you're not trying to cover up the behavior of materials, what you're trying to do is expose us to so many different options that we can see that we have a choice to accept and reject materials.

Seetal: But I also think it's just if we have to accept regardless whether we like it or not, or have a healthy relationship towards it. Because if we accept that it's a relationship, which is not necessarily healthy, that's a form of acceptance, or like, Okay, this is not healthy for me, I accepted, but I'm not going to integrate it. It's not going to be integrated into my life in that way, where I'm going to give it all of my attention.

Uzoma: Yeah.

Seetal: And that distance, therefore is necessary, you know?

Sheila: Yes.

Seetal: And I think, for me, it's all about accepting differences. And that's with everything, humans, plant, animals, you know, materials, everything. So, it's different that we are different. We can be. just because they're not similar to us doesn't mean that we reject them.

Sheila: I was just asking what material right now that if like, out of the ones you're encountering, or you've been encountering recently, which one speaks the most about your own capacity to accept difference?

Seetal: That's a great question. I think it's plastic honestly, at the moment, and has been for some time, I think because it's totally bastardized. But it's the material that is so intelligent and offers us so much, so much. And it's just pushed into a space where we're blaming the material for our behaviors.

Sheila: Yes, absolutely. Yeah, I was just as you were talking, I was like, why do I see plastic or something dumb? I don't know why, but in my head, it's just something that's so like, because I see so much in the trash. Maybe that's why, right?

Uzoma: Every time you say plastic, I imagine a Nestle water bottle, like an empty Nestle water bottle.

Sheila: Yeah, just on the side of the road.

Uzoma: Yeah. Yes, but that's actually not what it is.

Seetal: No, because it's not plastics fault, it’s that there is us putting it there, right. So why should plastic be blamed for our misbehaviors?

Uzoma: We keep running away from the keep running away from ourselves.

Sheila: Well, we're not comfortable people.

Uzoma: At all

Seetal: It's the worst. Which is something that I'm working on Actually, I'm wanting to kind of develop a materials birth certificates and materials passport.

Sheila: Oh, my God Seetal.

Seetal: Then a will also. Yes.

Uzoma: Wow, exactly. this is the anointing I want to tap into just from everything. I feel like, you know, this is also what we're aspiring to. It is like, the metaphor is a method, exercising and creating, useful constructive metaphor…

Sheila: Yes, an alternative world, it's not just like an alternative story or image, it's an alternative world so that whatever you pull out of the world is already part of this, it's never even if you're telling a story just about the passport, you have to understand that it belongs to a world. And I think how whatever energy you put into sustaining and making that world believable enough that we're interested in the story of the passports is like, it already in effect proves to people that they can actually put energy into building alternative worlds and survive.

Uzoma: I like that reading of sustainability as not just sustainability in terms of, you know, we hear that we hear the word, it's a buzzword at this point. Climate change sustainability, but also, I like that you sustain in that sense. So, it's also like sustaining narrative, sustaining world building. You know, I think that's cool.

Sheila: I'm just seeing and I feel like sus like its word for holding, like sustainability, suspension, sustain. I think the prefix is so much about… I just imagine a pillar, like being a pillar for something. And that's kind of matter right now. It's like, it's a pillar for this. You know actually I was going through your pictures, and I was seeing all these, I was going through Instagram, and I was seeing all these pictures of these different materials. And I just thought, I just heard them in my head being like, oh, my God was so excited to be here. They were so they were like, yeah, at least I mean, somebody notices us like we're actually doing a lot guy. Thank God.

Uzoma: I feel like, that's just, this is the work that you're doing Seetal I think, I feel like it's getting to that point where we don't live in a …. it's getting to a world where materials are not shaking that people notice them. Because wetness is the harmony is just there. So, it's like, yeah, do you understand, lts getting to a world where I'm not considering of plastic as just an empty Nestle bottle at the side of the road. It’s like, I'm fully in fellowship with all the things that I use and that I live with.

Sheila: So, you're saying that the world is becoming more aware of materials?

Uzoma: I'm saying that that is the work that Seetal is doing, and that is the world that is being created by this work. And it's a matter of time, before we get there.

Sheila: It’s a matter of time.

Seetal: There we go.

Sheila: Wow the heavens just opened. it is a matter of time and I think it's a matter of time because time is the matter, time is the matter.

Seetal: Exactly.

Sheila: We have to, now this podcast makes us realize we actually need names all other podcasts. Time is the matter has to happen. I mean because, and it's one of those things where time has to stay. Not has to but there's a reason why it escapes that tangibility that plastic has or that tangibility that humans have? Because like somebody has to do the work of being in graspable because that's part of what keeps pushing our boundary of our imagination. you think you know time and then Time goes and does something else and you're like, oh, time you're so sneaky I didn't know that I was capable. I Didn't know, even algae are probably surprising itself. like shit. I did not know. I could be… or like seaweed. Seaweed is like we are now snacks? Guys.

Seetal: Yeah.

Sheila: Yeah.

Uzoma: The tree that you talk about that gives us its pigment, its dye in 10 years. I'm guessing your own book. You know what I'm talking about?

Sheila: Is it Palo Santo? Yes, biosensors smell. But it's No. It's about the history of Polish scientists like how it comes from this tree, and it has to die on its own. And only when it dies. And then it now decides that it's ready to give off this smell is where you can actually if you kill it before, it's time to try and get the smell you will never get it.

Seetal: I mean, there we go. That says everything. No?

Uzoma: Facts

Sheila: That they have agency.

Seetal: Exactly. I mean, we talk about animism and all of this right? I think it just goes to show that they are beings in their own right. So yeah, we just need to form healthy relationships towards them, honestly.

Sheila: Heal the world.

Uzoma: You mentioning animism reminds me of what we were talking about earlier, about formal versus informal, East versus West. This is like the binary, which, obviously that binary is a very colonial construct, but I was just like, wow we were actually animist outchea back in the day. And then just whatever disregard we have for the materials around us, are born from just like this place that we've gotten to know, like completely disregard your animistic past or whatever and forget about that. And forget about this idol worshipping and like focus on the lights. And, you know,

Sheila: I think that's the thing about organized religion. Let me not speak for anything in particular, let me know if I'm cough cough and I'd love to throw shots at my people but I’ll reach you guys later, but organized religion. I think what it is sometimes is that it poses as a solution and doesn't allow alternatives. And then in fact, goes on to challenge and demonize any carrying alternatives because I feel like animism is an alternative that's carrying a whole chest of alternatives.

It's like you want wood, there is wood. you want stew, there is stew. you want water?

Seetal: Exactly.

Sheila: Go for it. But then this one is like ban anything that makes you think that anything else is even possible. I think there's so much. it's funny that we call thinking like that a version of modernization, we call that in civilization. And I think we do have to enter that realm of thinking of that as civilization so that we can learn from our mistakes and say, shall never again like this is know how to be civilized.

Uzoma: Do you know that in the Igbo world view everything has a Chi like it's not as clear like everything?

Sheila: Yes. Like in the Yoruba worldview, how everything has an Oriki, which is a praise song that is a sung about the essence of any being like, each element, each cloth, even fabric, whatever it is, it has an oriki. So, I think we just had to stop trying to prove to people that We've been thinking ahead, we just have to do more to keep putting energy into what we're calling thinking ahead. we need to put more…Like we need those passports we need. We need Indigo to have like bank accounts. I need to know what currency she exchanges. I'm curious.

Seetal: Yeah. We'll get there, I mean there’s many things were developing, including a material, horoscopes, and as a form of divination involved. And, yeah, it's really fun but also very informative. You're just really learning about yourself.

Sheila: Yeah,

Seetal: That’s all this is. This is our journey.

Sheila: Yeah. This was great way to close.

Uzoma: Yeah, I just I wish I could, I’m expecting that meme, we shall watch your journey with great interest for your career, I don't know what the meme says but I don't know if you know the meme, or if this is just me.

Sheila: No, it's just you

Uzoma: It's just me? Okay.

Sheila: It's just you. Thank you so much Seetal like this has made my morning it's just, it's wonderful. I'm so grateful that you are, you've made yourself present in our presence.

Seetal: Thank you so much. It's been an absolute pleasure.

Uzoma: Thank you.

Listen to Podcast

Sheila: Have you looked at Matter’s Instagram page?

Uzoma: Yeboo

Sheila: isn't it just amazing?

Uzoma: It is.

Sheila: I'm smitten.

Uzoma: Yeah, I'm looking at material Atlas just now. It's just…

Sheila: So even the book in person, is such an amazing piece of literature to exist. I have so many questions.

Uzoma: Yeah, it looks like it. I'm excited. Why are you laughing?

Sheila: Cuz, you said it looks like it, and it's obvious.

Uzoma: No, it is.

Sheila: You know, I just also realize the importance of photography.

Uzoma: Cause of the photos on the page?

Sheila: I think it's so interesting that sometimes, the essences of some things may only come through when they see it through the lens of the camera. Like, if you put it to them in person like that. They may just be like, these are just a couple of verses, but then when you take a picture, it’s like “Oh, I feel something, which is interesting.”