Art in a Broken System, a conversation with Chigozie Obioma

Booker Prize-finalist Chigozie Obioma wrestles with art’s role in a Nigeria where survival trumps ideology. He contrasts Western abstract struggles (like pronoun debates) with Lagosians praying over untreated wounds, asking: Can literature matter when pure water costs more than hope? A raw, urgent dialogue on who gets to dream—and who’s left clinging to faith as their only lifeline. "Writing won’t fix Nigeria’s roads, but it might keep the writer from crumbling."

5/8/202435 min read

In this raw, winding dialogue, Booker Prize-finalist Chigozie Obioma grapples with art’s impotence—and necessity—in a Nigeria where "pure water costs more than hope." Between laughter and despair, he dissects:

The Elite’s Bubble: How writing about 11th-century Igbo kingdoms feels like "arranging deck chairs on the Titanic" when 170 million face collapsing hospitals and highways-turned-rivers.

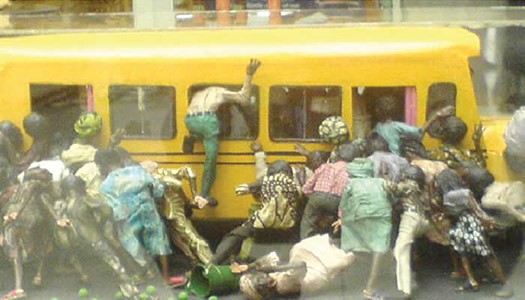

The Okada Man’s Reality: For the motorcycle taxi driver praying over a leg wound, "white supremacy isn’t even on the map"—survival eclipses ideology.

America’s Abstract Battles: His Nebraska students "take depression meds over Trump’s tweets" while Lagosians starve. "Pronouns vs. pure water—that’s the chasm."

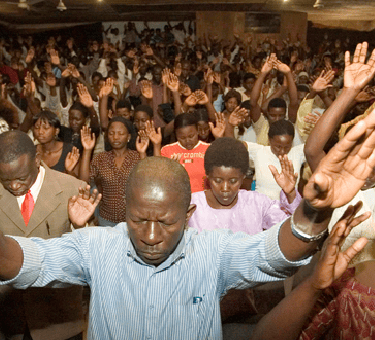

Faith as Lifeline: Why churches like Dunamis thrive: "When the state abandons you, God is the only ‘daddy’ you can call."

Why It Cuts Deep:

Obioma’s anguish is visceral—a man straddling two worlds, where literature "can’t feed the hungry but might save the writer’s soul." A haunting meditation on who gets to dream.

"In Nigeria, art is either oxygen or opium. Sometimes both."

Read Transcript

Chigozie Obioma: While two layers of existence are accessible to anybody, there is a layer of the abstract layer, and then there is the concretized palpable layer, I think. So, the concretized palpable layer is what I saw as I was coming into this enclave of welding in Lagos, Lekki. It's all flooded. It's like wading through mud, mudslides, like Bangladesh type of place, even though this is, you know, Lekki. So, the concrete reality is one of abject poverty and sometimes hopelessness, for the most part.

But we, the elite class, think more in the abstract. So, in the abstract, this thing that you're talking about, you know, me writing about 11th century Igbo and as, you know, American elite class would call it, centering a particular discourse. None of these things matter in the scheme of things; they are there to entertain, yes. We put stories out there, right? Let's say I win the Booker Prize. But on the whole, the woman who is selling gari...I saw a lot of people walking in the rain. There is no shelter. What does that do? How does that improve the lives of these people? It doesn't; this is a fact. So, I have to tell myself the truth. Yes, I'm doing all these things. My pocket is being lined. I have a name, I have recognition, I can. Sometimes, I get bullied when I come in here. You know, as I was entering Nigeria, I was asked if I was IPOB. You know, I don't know if I support IPOB No because of your name. I guess I criticize Nigeria; some people know me. I guess I used to think I would just enter, and nobody would say anything. But now and then, like, twice now, I've been asked certain questions. You know, and it happens. My friend, Okey Ndibe, has said some as well. So, I mean, it was a quick question. Oh, Chigozie Obioma, do you know? What do you think about IPOB? I'm like, I don't know, what are you talking about? I've never met Nnamdi Kalu or had indirect contact with him. You know, but I did not find the guy very impressive. I think I mean, I, of course, I think that ideologically, what is trying to do is, in some ways, the right, you know, the way forward. Again, as I've said, dividing the country might be the way forward, but I don't trust him; I don't trust that we will have new leaders; they will just emerge out of the meters and start changing things. Right now, the leaders that we have if you go to Al-Igbo are, all you know, not doing well. In my state, the guy we have named is Ikpazu. And this is Ikpazu. You know, He is a great idiot. So, imagine that we have Biafra, and that guy becomes some kind of, you know, pressing opposition. So, will he magically change? Just because we have what maybe you could say that there will be some kind of infrastructure that might, you know, scaffold him in, and he won't have the leeway he has now. But until I see that, it will be the same thing. So, yeah. This is just to say that all of these things that we are writing and doing, you know, these artists come and dance for Europeans, all those people, it’s for them, you know, is not for the common man who is the bigger population of society, the people I'm talking about makeup or at least 170 million, if not more, you know, of this population. So, it has no meaning to them. I could write I will resurrect 10th-century Igbo land. It does not mean he has been familiar with, of course; many people are interested, people like you, people in the diaspora, and others curious about the West, but it ends there.

Sheila Chiamaka Chukwulozie: But I need to go back to this thing of you saying it doesn't matter. When you say it doesn't matter to the majority? Yeah. Is there any? Is there any work to you in your way that has changed your state of existence?

Chigozie: By the way, it does matter; literature matters. I'm not. I cannot be right now; I'm judging the Booker Prize. So if I say the literature doesn't matter, and you put me there, it will be a major hazard, And this is Chigozie Obioma. So it does matter, but I don't know if you catch my drift. What I am trying to say is, yeah, because our problems are problems, they are not theological. They are not ideological. So, in the West, I teach at an American University as a day job. You will think that I'm joking, but some of my students, in fact, most of my students, I've realized, even though I have refused to go to the American East, in the Boston area where they have the high leagues, I have remained in the Midwest in Nebraska, it's an unknown state, you know, just because I feel like okay, at least the pool of students we get have not been completely radicalized ideologically, either way, I'm not talking about the work left or the conservatives. At least these are, you know, for the most part, in the center, commonsensical people. But I'm finding that in the past two or three years, I am getting a flood of radical students who think that the world's greatest problem is pronouns. She did this, he did this. No really. They believe they work for sure, and the grid crisis of their life is this: the second crisis of their life has gone now, Donald Trump, you know, on his tweets. Hence, an American president who may or may not be mentally challenged wakes up and tweets, we must build a wall, and then he puts like five exclamation marks, and then some people start taking depression meds because of that, you know, and so, I mean, this is their reality. So they have the time to think about this abstract. If you look at these children, you're 18 years old, you have a car, you know, you have your parents, and some of them are riding with BMW. Know that your parents are paying your school fees and everything, or some of you take loans that you will pay, and your life is good. You're in the number one country that reads every other person out. And you think that you're you have extreme problems. And this is your problem. So, is it farcical comedy?

Sheila: Is that not their reality?

Chigozie: Yes, that's what I'm telling you. So, they have the privilege to live in an abstract reality, where they then invent new problems for themselves. So, they commit suicide; almost every year, at least one student at the University of Nebraska throws themselves either into the highway or some kind of thing. And most of them are ideologically linked. So that's what I mean. So, if you are in that realm, some of them are people in Lekki or VI living in that reality, even though most other people have serious problems. You have diabetes, and there's no hope of ever going to a church in your life or, sorry, a hospital in your life because there's no money. I was dragged to a church on Sunday. And it was sad I shed tears. So, a guy who has leg pain, no shit, leg pain. These guys said that he received a miracle, and now his legs, you know, are fine. So, he prayed. He fasted because of leg pain. So, it never even crossed his mind for one second. I wanted to intervene, but I wasn't allowed to. It never crossed his mind for one second to go, you know, to the hospital, his leg, what is wrong with him? No, the only trust and hope he has are in some guy who says he is a man of God and has supernatural powers. So, this is the level of depravity; it is already not the depravity or deprivation we are discussing. So, in that reality, literature, music, arts, philosophical thinking, and ideology are luxuries. Do you see what I'm talking about? So that's that's the point I'm making, but they matter, I hope. I mean, I hope that my two novels are serious works of fiction.

Sheila: Yeah, so serious because Even in this realm, especially, I mean, I think I'm asking this question too, because as someone who exists, which is what I was thinking in the beginning, I'm happy I was here, like, during this period of these degradations, let's see. After all, the way that my body felt it and the way that my body has been indicated, in just the sorrow of being a Nigerian, most of it comes 80% of my body's depression starts from my mind. And it's like saying that what helps my mind has no room in a place where material suffering is what I experience every day. Like, I can't, I can't read myself more, but I can read myself into understanding that Nigeria is what's fucked up, not me. And I, as a person, am connected to so many other lineages of things that are not fucked up, which is actually what gives me. It gives me something that allows me to say, I'm not going to rip you off what other people are saying, but it is Nigerian to rip people off. What are you doing? Yes, you want somebody to just take you for a ride, like that experience many times. But when I read things like the abstract that you are talking about, that then helps me; I skip this time, like I can skip the concrete time and imagine that there was actually once upon a time, even if that's a fictional thing, that once upon a time is actually a grounding in a time that none of us even know. It's like nobody can tell me that that time did not exist because you were not there. For you to be 60 years old means that I am imagining it wasn't at that time.

Speaker 3: So this leads me to go back to what you were saying earlier about the ideology and how that is more relevant to the majority of people right now thinking about this material modality that seems to define and set the pace of our lives, especially in a place like Nigeria, like you rightly pointed out with, the way we approach religion and all of that, and also thinking about what you just said now about your mom and not going back to making that, like, imaginatively, back to times past. I'm just wondering what you said earlier about the psychological, the ideological, and how, like, isn't there still that is that necessity because it is until we address these ideological... it seems like gaps are until we address the gaps that we can then sort of solve the sort of breakouts of this trap of material modernity, that We have found ourselves in. So in that way they are very side by side. Yeah, what do you think about that?

Speaker 1: No, I agree with you. I think that not being able to...even though we have privation and whatnot, we should be able to think, is still in the abstract; I think they should; we should be able to vote both with our two hands. But again, there's a lot of material that we are overwhelmed with. The modern African is overwhelmed. I have children now; one day, I went into my daughter's room when she was not even six months old. And it just occurred to me that this lady had this girl who had more clothes than I did. You know? No, it's true. And I'm her dad. And she's not up to one year in the world. And I've lived all these years. Thank you. So I was just like, What did I have made do with in Akure in those days? There was one ball with which there was our design, and then there was a poll, I can't remember any other thing that we had, you know, and I turned out okay, but this girl has to have everything, you know, she has to have the thing with would you pump mucor out of her nose? And once I, you know, I said to my wife, I'm like, look, we're not doing this. You don't have to buy everything, I threw out the pump thing, and if she has this thing, I would suck it out. You know, we get it out somehow.

Sheila: We talked about how I was younger when I was 10. I went to live with my aunt to save money to travel. And I used to take care of her baby. And I was like, I remember I used to change the napkin. But we would wash it, use another napkin, and then use a safety pin. And I thought that was only just 17 years ago. For me, it seems like I dreamed it up. I don't know any more babies, not even those I see in the markets. I don't see any baby wearing napkins. And I'm trying to think, like, what? Yeah, because I don't know, some things get discontinued because they're bad, like, you know, that they're not good for something. I don't have a reason why those napkins were so discontinued. Could we have even used them side by side? I'm so confused.

Speaker 1: Yeah, so you're right. And that's. We are overwhelmed with material things, which forces us, especially if we don't have many of them, to think a lot in just strict and material terms. This is why, again, in the West, especially in academia, think of some of my colleagues, for instance, if you're thinking of how radical you can be, like the Okada. Style radicalism, in strict political ideology in the length...so the academia is the enclave of some people like that. And then you sit down, you think, Okay, why is this guy like this? Why does he see the word strictly in these terms? It is because he does fame studies, and he earns about $100,000 a year to do what? Bring a couple of 18 years to come and sit in a Porche class and watch him. And then he doesn't have kids. He believes that climate change is why he doesn't have kids. He has his dog and girlfriend; what else does he need to do with all that money and has nothing? What is the joy in the light? So the only thing they can think of is that he has everything he wants to watch a film now that people have his fingertips. He has an iPad; he has all kinds of things. He taps two buttons and is, you know, watching the most ... film that came out five minutes ago. So this guy is overwhelmed with money, so they don't mean anything to him anymore. So, all his thinking is in the utopia that doesn't exist. How can we have a society in which there's no racism? It is impossible. This is cosmic justice. You can’t root evil out of the heart of a human being. How can we have a society where there is no misogyny? Again, it's extremely impossible. So, he spends all his time thinking abstractly because the matter is overwhelming. He has everything he needs, but they mean nothing.

Sheila: I have a question.

Speaker 1: So the guy craves material things, thinks about them 24 hours a day, and has no time to think of, you know, ideology. And this abstract so the American leftist professor can spend all his time about Freud. And, you know, Foucault.

Sheila: When you talk, you sound like you don't believe what I am hearing; you dont believe what he is doing is worthwhile.

Speaker 1: They might have some points. But yeah, I'm just trying to make a comparison. To answer Uzoma's question about why, I think the ideal thing would be to have both an abstract mind and a material one. But, you know, even in the West, some people cannot have both, is what I'm saying. So that's the reason why I'm making the analogy.

Sheila: Chigozie, my question is, do you think the crisis of modernity is maybe a crisis of desire? First of all, what do we have that we do not desire? Or do we not know how to desire as a people?

Speaker 1: We have a spirit, mostly too. Of course, it's not easy to speak in general when talking about people who are complex and diverse in their thinking, but I think we have a spirit that I admire. It's a spirit that can withstand; it’s not easily crushed. Some people call it resilience; some have attacked me and said we don't have that blah, blah, blah. But I think we do. I see it all the time. I have seen people, extremists, in poverty who do not have the kind of spirit that we have. I think it comes from, predates Christianity, comes from our tradition, different at least I can speak to the south in general, the Igbo, Yoruba traditions that I know very well, that there is the idea that one must, that everybody is unique. And, you know, whether it is your Chi or your Ori, you are unique because you have a promising future awaiting you; you just need to grab hold of it. This is also why the brand of Christianity that has taken root in Nigeria is very powerful and effective. Because they are using some of those tropes that come from our religion, so this is why a Nigerian would see that people have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea and decide, Well, you know, yes, they told me that people are dying in that place. But there's something special about me: I will reach my destination if I hop on that boat. I don't know if any other people would think like that. You know, I've done this. So it's a psychological, deeply philosophical thing that is unconsciously embedded in us, that you will not, an American will not think like that if they know that is a concrete reason to be afraid of this and either they are doing it in a suicidal way, they are just giving up on life or they would not. A Turkish person will not do that either. A.. which other people have I studied very closely? Even in Africa, a Ugandan person will most likely not do that. This is why they don't take the immigration risk we take. So, that is extremely powerful. It does lead us to do things and achieve certain things that we, you know, others may not achieve, but it also has its cost. It can lead to foolishness, you know, and a complete waste of life. For instance, I've given where people just die, but I think if you want to look at the pros, there are more pros. Still, it also leads to a lack of humility and pride and selfishness and ego that you see, you know, like, Me, I am the Oga, everybody must bow for me. I have to play in this thing. I have to own this. So it's surrounded, a life that Darkness surrounds, but again, if you depend on how much light, you know how much you feel, it can always overshadowed. So that's one thing we have that we don't appreciate, I think.

Sheila: But on this note, into the book, does that mean that what Chinomso did is more of a pro than a con?

Chigozie: Yeah, so that's an example of that. When I was in Cyprus, we would tell Nigerians not to come here. And not one person will listen, they'll be like, oh, if you dey there wey you dey enjoy my guy, you know, na ebe say if we sef come. You know, we're not gonna pass it, you're telling them this, they will not, you know, they never listen. So, what Chinonso did was a little bit different. Of course, it’s an act of naivety to trust somebody he doesn't know, which many of us also do. But it is also in that belief that somehow things will work out for him, you know, Christianity has amplified that everybody believes that, if I go, you know, this is in the church again, on Sunday, they did something that I don't know that you can see in most American churches, except maybe in the south, places like Texas, with Joel Osteen and the rest of them. Everybody was making claims about themselves, about this being my year. I promise this will happen for me and will work for me. No Christianity, because it is a call to remove yourself; you have to die to this self-issue. I'm saying that you do not exist; you are in service to your Creator. So whatever he gives to you, which is usually a cross, is what he asks you to carry. So, here, again, it's a very different environment and psychological landscape. And, of course, a Nigerian cannot understand the theology of selflessness in the philosophical landscape. It's irrational and stupid to him; how can you say that? So, it is absurd, but that is a true theology. But we are not; we are not deep when it doesn't put us necessarily in a completely, you know, outside the zone; others do it too. If you look at Christianity in America, for instance, they do not have the Jamboree and the dancing, the praise and worship that we have here for the most part. Why? Because the western person is more sober, is not as this, so you go to their churches, and they all calm you know, even when they are doing their music, nobody dances falls to the ground that we do like, do you think that you were like in a party dance hall, no. So they brought their temperament into pieces. So everybody mixes it, you go to Italy? Roman Catholics, you can show them the scriptures. Hey, you must not make a graven image in my likeness. What are you talking about? For centuries, anything that they adore? They replicate it in their art; they make statues for all the gods, whether it is Zeus or whatever. And then now you give them Christianity, and you say, Oh, no, we can't make statues for him? My friend, you're not making sense. So they make the statues anyway. So everybody takes their own. So, they receive a particular ideology or religion. They, you know, localize it, and it becomes something local to them. So, they are Christian in Nigeria; is this not what is obtained elsewhere? In fact, it is strange to somebody who is coming from, you know, Latvia, who reads the Bible. No, you do not have the same understanding of God as those people. So yeah, this is to say that there is a localization that happens whether consciously or unconsciously, that you know, we don't sometimes we don't, we don't remember, but it happens everywhere. It happened even though there was a guy who was a friend of mine from India, and he told me one time that he had become a Christian; I'm like, okay, that's interesting. So what has he done? Hindus have 9 million gods, so he added Jesus to the list. He didn't need to do anything. Jesus is part of this thing, so it didn't take him anything to become a Christian.

Sheila: That's an honest guy, a real one. Uzoma, do you have any questions?

Uzoma: I do. I've been wanting to ask this one and just on the load, so I watched your talk from the Igbo conference last year, Then Lose a Billion; you talk about writing an orchestral minority from an Igbo worldview. And reading the book, one can see that. And this project that we're trying to do that we're working on, our research project is about contextualizing Igbo proverbs in like giving it a sort of 21st-century lens and seeing how it can be relevant to us, here and now. But I feel that one of them, something that has been almost, I don't wanna say blocking, but it's something I've been aware of, is that, how do you approach a challenge like this, even knowing that you are operating from a Westernized world view cause that's something that you also acknowledged in that talk that whether we like it or not, our baseline is Westernized just by occasional by virtue of the world that we live in how things work. So, how do you approach this in many ways? We're trying to bring Igbo world relevance to the 21st century, but how do you do that when you're almost trapped within a Western mode of thinking and being?

Chigozie: It is almost impossible, my brother, it is almost impossible. So this is what we've been talking about; what we are trying to grapple with can only remain in the domain of the abstract, for the most part, because, again, the material reality is operational in reality, and it dominates here. In the West, material reality does not dominate because it used to know what dominates is ideals. This is why in American politics, let’s say the last election, it does not matter that under Donald Trump, the economy was the best it had been for time. Nobody gives a flying. Forgive me for my language; no one gives a flying fuck about that. It doesn't matter whether the 401k, like my stock, ballooned daily. I am the one guy who would never care about these things, but I will be like that. I've become like a, you know, a Wolf of Wall Street. Before. I sleep for almost 30 minutes daily; I watch what is happening; it's rising, and nobody cares. This guy insults people; he doesn't know how to talk. He's supposedly a racist; he’s a misogynist. This is what matters. But here, you can be the worst human being in existence. If you can give us good roads, you give us security. Who cares? Like how you behave to other people, which is none of my business, but make the lives of my people good. And nobody will do so, but they have the ability to think, you know, in that way; I mean, of course, we will care if Buhari insults people. But the dominance, the hierarchy, the dominance hierarchies, is what I'm talking about here. It's like light and day, so because of that, most of our discourses, things like things that are even philosophical, will just be subsumed under the material reality of the West and their ideological realities. So, for instance, if I'm writing this book, and, you know, when I first told my colleagues again to use them as an example, I'm writing a book about this. They loved the idea of the Indigenous culture being resurrected, as you know, as a middle finger to, you know, the West and colonialism and all of that. But Chigozie, is Chinonso a misogynist? Does he have toxic masculinity? So, they still brought it somehow and subsumed it under their own, you know, ideological orientation.

Sheila: So, is that ideological warfare?

Chigozie: Yes. So we still have to submit to the right. So, I’ve been working on an article, Forever, the essay's title for the Atlantic. The Decolonialization Movement suffers from epistemic poverty. That is my main point. So we say just in conclusion that, okay, so we don't like colonialism. And our founding fathers Azikiwe, whoever, blah blah blah, Awolowo, they all fought tooth and nail, let us get rid of these white people who were like dominating and taking, and you know ruling us. And once they did that, what happened? Very, very interesting things happened. It did not occur to any of them. That's Okay; now we've gotten rid of these people, how about how we used to live? And how about our socio-political structures? How about our own culture and religion and all of these things? How about just the things that are isolated from this dominant culture that was imposed on us? No, they said, you know, we've gotten rid of the personnel, who were, you know, orchestrating and directing this civilization, but we must retain it. And even today, how many years later, our ruling class tells us that colonialism was a great thing because Nigeria is a product of colonialism, and we have to maintain it. And on the other side, they said, no, we don't like colonialism. So you see, the incongruity was, there is a word there, So there is a cognitive dissonance,

Sheila: Dissonance, yeah.

Chigozie: Of what they are arguing for. So, if truly we do not like colonialism and all of the things that they brought, why should we insist on maintaining the structure? It doesn't make sense, and it's irrational.

Sheila: So what? I want to let you go; this will be my last question. Uzoma, do you have any likes? Can this be our roundup question?

Chigozie: It has to be my friends; it has to be. Okay. We can continue by email, but I need to, you know, go.

Sheila: You have to take care of your life. That's fine. In all these things you're saying, I'm going back to the beginning of the conversation where you were thinking about the Okada man and his reality. And if you get back to your points, it's almost that what he wants may very well oppose someone else's idea of what makes sense to be wanted by another person. Yes. How do you who come from a different time, let's say you teach in New York, or you teach in Poland or Greece, then come back here? And having experienced their desires in that space and coming and seeing our desires? How do you hold those two worlds? Both the abstract and the concrete in your hand? And how do you balance it for yourself? Because to ask how we should balance it? I mean, who knows? But how do you do it?

Chigozie: Well, I think that in some ways I do balance it, and this is, I think, because of, you know, I have had some fortunate things; my education, I have to say, is part of why I can. This is why I'm not beholden. You were making a point earlier that I do not subscribe to the ideology of the, you know, of the leftists, of my colleagues, a dominant and very, very, very, very dominant and almost intolerant ideology that the elite class in America holds. It is because I cannot; there is no time when I can submit to a particular ideology. It's now impossible for me. So, I have developed a mind and a psyche that is able to divorce my own opinions, my thinking, and my impressions from those of others, so I can tell you I know a lot about Christianity. I know a lot about Islam. I know a lot about leftist ideology. I can tell you what they think dispassionately without criticizing it, so there's an objective way of viewing the world: the education of Americans; this is where it fails. So I am, I think, in some kind of. This is what I respect about Nigeria in the 1990s and '80s. I went to school here. Yes, you could say that they were elite schools. From the beginning, I credit my dad, at least, for that. But it’s still Nigeria. I have taught at American University and interacted with many Americans for a long time. And British people, all kinds of people, I can tell you that there is poverty in how they see the world. That is a serious problem. For instance, I tell them, " Look, they asked me, okay, we go to a literary festival. And, you know, they’re all jumping from one place to the other listening to what these writers, and I never do that, then my agent asked me, Chigozie, why don't you come? Let's go and listen to this panel of this thing, And I would always say, look, I may not know you, I may never have heard of you before, I've not seen you. And I can tell you what this person will say about every copy. I could quote let's try it. Ask me one of the questions they will ask that person. And I will tell you, this is the answer they will give whether or not they believe it. You can say political correctness or whatever. But this is what these people think. So it's not different. So you could have been replicated by 1 million. Everybody will say the same thing. So, nobody seems to have anything unique about you, and you are right? You're an intellectual, nothing. It is like a robot placed in the center of this really unusual scale. So, what is the point of listening to this person if you ask them now? How should we write about Africa? We have to center blackness in this thing. this is what anybody will tell you at any time, you know, at any place. So, then, what is causing this is a poverty of education; they do not; people no longer have the ability to think in a critical evaluative way; this is not critical the way they see critical. critical, which is just to try to put everything down cynically. No, you can look; I can tell you that this place is black, like this color, the color of this chair is black. And you look at it with nuance, and you attack it, you observe it from every angle, you go around it, psychologically, you walk around that thing, the education that you have in America, even in Harvard, students cannot do that. So, again, this is why they would join an ideology, so somebody thinks for them. Okay, our name for Latino people or black people now is Latinix. Okay. Where did it come from? Nobody asked any questions. You will see the next day at the faculty meeting. Oh, the Latinx people have said this and that. And it will not even cross anybody's mind to ask, where is the provenance of this term? Where does it come from? How did we come up with this? What does it mean? What ramifications? Nobody asked anything. So, it is the same theology that the Okada man embraces unquestioningly. Do not mean somebody says that they were permitted names. Everybody shouts hallelujah. They were like 25,000 people, they said; I asked the usher later in that place, and not a single person questioned whether or not it was possible, and they showed the video of the nails. Where is the blood? How is it physiologically possible? So, there is an inability for both the educated elites and Western people inability to look at things in a way that is not. that's why they embrace dogma; the worst thing you can do in my school now is come and give an opposing view about anything. If I come now and tell them, look, white supremacy is not the worst crime or racism is not the worst crime in the world, it's murder, it is rape, it is any of these things, everybody will freak out. They will not start thinking, " Oh, is there any sense, and what am I saying? Can we empirically measure what is worse, that somebody, I'm going on my way, and somebody is calling me a monkey? Okay, you call me when I can call you back. Your father is a monkey, and then I go my way. How does it physiologically affect me? It might demoralize some people, yes. But you know, I mean, I am a Naija guy, it does not. In fact, I can even slap you and then go my way. Is it worse than you robbing me? No, they will tell you, No; the robbery is nothing compared to the racist abuse, quote unquote. But is it true? So this is the thing, so I think I have to be; it is very difficult now to hold both the abstract and the material. This is why American elites lose the material and take just the abstract. Nigerian Okada man says the material and forgets the abstract. I think you need a very, very strong education. And you need a sense of integrity. I am not going to fall, you know, into some kind of ideological; that's why I always tell them to look. I would rather ride Molue in Lagos than say what I don't believe in, so when they come, you know, people tell me, okay, come and join, so and so thing, okay, what is it about?

Once I see it, Okay, you're fighting so and so thing. Okay, there is oppression here. All right. If it doesn't make sense to me, I tell them thank you. I'm not that participating. It does not matter what you do to me; you cannot read my book, and it doesn't matter. You can't tell me not to come to this. None of that matters. Suppose it doesn't make sense. So you have to stand on some principle. If not, you will. They will just be pushing you around, you know, like ball tomorrow. If they say okay, they will challenge your view on a particular thing. You apologize quickly and then align with what they want you to do. No, you don't do that. Don't do that. Thank you very much, my friends.

Sheila: We are transfixed. This is what they should have been preaching at Dunamis.

Chigozie: By the way, I like the church. All the best to both of you.

Uzoma: Thank you. Same to you.

Chigozie: Alright bye

Sheila: Bye

Listen to Podcast

Chigozie: No, but that's a comfort; I see what you're saying. It is good. But again, I say bring it back. So, I think I'm taking myself out of the picture if I put myself in the picture. Of course. I have a lot of, you know, I can take myself on and go back to all those times. And you know, luxuriating man, and this is what I love to do. You know, I tried to write a novel about the 11th-century Igbo land, and I did, and it affected minorities. Yes. But again, I think I've just lost the ability to take myself out of the picture. And all I think about, especially when I'm here, is the people I see daily. See what I am saying? I'm just thinking about the reality. I asked one of them the other day, in the scheme of things. What, where is white supremacy on this scale of your problem? No, it's true. So because, you know, if we go through this thing, I tell you know, Americans will be like, white supremacy is your number one problem because it is the thing that is killing you. It is why your country is like that; they say that it is the great evil racism, somehow, okay, what, on what scale one to 50? If you were to name your problems in white supremacy, and they're like, What are you talking about? It doesn't even appear. You know, on the minds of some of these people, you could, of course, make the argument that they are not thinking in, you know, extreme critical times, some geopolitical problems are informed by white supremacy, but that would be a stretch. Indeed, white supremacy does not appear on their radar, but I will tell you, you know, that there is white supremacy, and it affects my being here. So that's what I'm trying to say. So, if I go into the mind of the Okada guy I was interviewing, I just can't see these things you're talking about. But I understand what you're saying. You see what I'm saying. So, there is a dichotomy of myself, you know, that I'm trying to pull here, and I'm, you know, becoming out of sadness. I am resting my foot more on the other one.

Sheila: What is the other one?

Speaker 1: yeah, the Okada guy the mind of the Okada guy.

Speaker 3: But how do you link them? I am sorry, but I am just coming in here. I don’t know if you introduced yourself initially, but I'm curious about how you link the ideology to the Okada guys' lived reality. Is there any link? or is it just a strict dichotomy?

Speaker 1: He is not living in the abstract. I'm saying that he has no time for ideologies. He does have; you could argue that his ideology might be writ large in his religious beliefs. They have to, like people often will say, say that the church is one of the comorbidities of Nigerian politics, you know, reality, well and good. I knew the church I went to was Dunamis. So, yes, it’s the big one in Abuja. So I used to see the brother of the guy who owns it. Eneche, the brother, is dead now. And when this church is now the biggest one in the world, it is the most expensive. And I'm so sorry about that. My mom won't let me rest.

Sheila: My own mum, too

Speaker 1: So, the truth is that the church, for instance, exists because the poor people made it exist, right? They need it to survive; they must be Christians. So they go to those churches and do it again because if you are sick, it's just you and your God. That is one of the reasons why if, if a guy who is a Mopol arrests you, and they can arrest you for just about anything and flog you, the only person who can save you is either, you know, somebody, or again, your God, you pray and fast. So, you need religion for people to survive in this reality. So, it’s not in the West, where everything is. What is the point of God? If you are if you truly want to pursue God in the West, then you know you should admit that you truly a spiritual person. This is why some of our Nigerians I know guys will fast here, they pray, they go to the mountain for 40 days and 40 nights, once they hit America, once they are in New York, they call me Chigozie I am in America o, the next day, you go and see them and be like Pastor, what is going on here? Forget about it, when you dey talk? We dey America, you dey tell me about going to church, that is when you know who is true. So it's a thing; it’s almost a psychological lifeline for them.

Sheila: This is connected to what we were just talking about, in terms of, like, how that line between psychology and physiology is quite thin because part of the reason they need that God is because the concrete is, like, where other people may have their actual daddies called, you have your own "daddy" that you call to help you alleviate the suffering of just being alone. And if something happens, you feel like it's not out of your control. You control this by being at the mercy of God. So how do we? This leads to my next question: what does your mom think about? I mean, now that you talked about your mum calling, I remember my mother because it's always so funny when our friends come around. She doesn't understand or can't explain. Yeah, she can't describe the mechanics of how I can survive by doing what I want because what I'm doing is invisible to her. I don’t know if it's incomprehensible to her. But it's mostly invisible to her because it doesn't in this reality. It should not quit my survival, and yet it does. Does your mom, because I don't even know, I don't know how your mom grew up, I don't know, does she have questions?

Speaker 1: She does. She does, and I often like to use her as an example, and my dad does, too, but they've fought me about that. In the past, she lived in a different reality than me. So, for instance, I, you know, write all this fiction. I'm very interested. So the topic we want to talk about is Igbo folklore, right, and, you know, metaphysics. I was interested in these things in concrete terms, but right now, my mom is not interested in them; she has found a God who, again, so religion here is directly linked to the material reality. This was the point I was trying to make.

In the US, religion is more linked to spiritual well-being. So the spiritual well-being here is probably something that people don't even think about, or they think about in a very marginal way; you see what I'm saying like it’s at the very least, so my mom is no longer interested in Odinani and the deep Igbo culture, even though she grew up, her dad used to be this one person who was seen as an evil family because you know how people do because they refuse to convert to Christianity, he was an Odinani guy until I think he was in his 60s. And finally, he went to church, and for the first time, everybody celebrated. So, for my mom, yes, my mom grew up, my mom was doing all these cheesy things that I know about, my mom was doing, my mom had her shrine, she used to dance for Ani and all of the goddesses and all of that but, she no longer does all that. So, right now, she doesn't understand why I'm still interested in those things. She thinks I'm insane for being interested in those things. And you know, the invisibility of what I do, as you say, you know, as you articulately said, there is also another factor. She thinks of my writing as an accessory to my job. So she tells people, well, my son is a professor. And they say, oh well, we know him because of the books he has written. And she's like, you know, what are you talking about? The book he's written? He teaches the books, you know. She is not very well educated, as you can already surmise from my statement. So, something has to be linked concretely to make sense, a material reality for it to make sense to her. So, she is like that if I remember one funny thing. When I went to the US the first time, it was based on, you know, I got into an MFA program, and I got a contract for the fishermen, and you know, all of these things that had no connection to anybody. So when I told my mom look out, I am moving to the US, she was so happy; she started explaining how her brother, who has been living in Texas for two decades, is such a good man that finally, you know, the one person he took is her son. So she was saying all these things how God would bless him. I'm like, did I mention this man's name in any of this? Then she said, are you saying that it's not your uncle who did the same for you? I said I had not spoken with this guy; you reminded me he exists. But you see, why did that tag come? She didn't believe till today that you knew you could go to the US alone.

Sheila: On your merit. Exactly

Speaker 1: I'm like, Okay, thank him, let him take it, I don't care about that. But I, you know,

Sheila: Since she thanked him and had that relationship, My curiosity is what she saw at the end of that life that makes her look back and say don't go there, don't go there.

Speaker 1: Well, she has not seen anything; she just is going with the flow. And I say this with all due respect and with love. I mean, she just sees that this is the new way. It is the so-called White Man, you know, white man's religion. This is what gives you a job. This is what gives you influence, and they go there. So, in an official minority, if I remember correctly, there's a path that I think is pertinent to this discussion. So the Chi is very vocal, of course, a critic of Western civilization, as well as the civilization of the Igbo people's traditional civilization. There is this point in the novel where it asserts how our people left, you know, the land of the, of the ancestors to the appeal of Western civilization, which was domiciled or realized in most of the cities, in places like Lagos, for instance, they all went there. And there has been, in fact, a radical reversal in the negative sense. For instance, you wouldn't see the Chi make the case. In the past, in pre-colonial times, at least in the southern Igbo area, there was it was almost alien for you to see someone who did not have a house to live in a shelter of some kind, that is, okay, you don't have the house live, I mean, the people will come and build one for you, everybody will bring a brick the one who can do the mud, they will all go and gather, you know, and build something for you. So, there was a kind of communal cohesion that, you know, was rooted, of course, in this shared ancestry. In fact, in the ideological principle that if you know you are living in a state of chaos, you create a kind of discord with the rest of the community. So they don't want Discord. They don't want chaos. So, they try as much as possible to ensure everybody is united. This was why, in Al-Igbo, there was no such thing as imprisonment. As the punishment for crime, this is an alien thing. It's from outside, Also the West. So some people don't know this; they call the people who were, you know, outcasts as slaves. No, they were not slaves. The worst thing that you can do, the worst punishment for a crime in pre-colonial Igbo land, was exile; you are severed from that cohesion of the community. And that is the worst thing that can happen because you are uprooted from the land of your ancestors. The link to these 1000s of years of existence is gone. So they send you nobody; even if you were to hang around the perimeter, nobody can buy or sell with you. So, you are completely ostracised and isolated. So that was what, and it's supposed to continue. You pass it down, too, so it's not like somebody in prison is putting them in some servitude. Some people like that started doing shrines. But the folks who were ostracised were not slaves. So I'm saying this just to say that in Al-Igbo before, there weren't the kind of people sleeping under the bridge. So once our people embraced what they thought was the greatest civilization, they formed urban cities and whatnot. Now, you see excruciating poverty, and you see homelessness that people did not have. So, the subsistence that was enough for people to live, take shelter, indulge in communal support, and just live and be was enough for them at the time. But now, there are conditions even though it seems to be in a, you know, they have material modernity, they are worse off now than they used to be if you get my gist, but my mom, for instance, doesn't seem to..., you know people here do not think, they don't look that back, you know, far back. They don't think comparatively. Okay, so the social condition that we need to live, exist, and live with. And if you compare them to now, which is better? I will make the case that even though we may not have had phones and TVs then, our people were happier than they are now.